Fitbit, Garmin and other consumer heart-rate monitors are increasingly being used in clinical trials. The problem is, they’re not always very accurate.

A search of ClinicalTrials.gov, the world’s largest clinical trials database, reveals nearly 200 trials involving Fitbit devices. Makers of consumer heart-rate monitors, however, clearly state that they are not intended for medical purposes. For example, Fitbit declares that their product is “not a medical device” and “accuracy of Fitbit devices is not intended to match medical devices or scientific measurement devices”. Similarly, Garmin makes it clear that its Vivosmart device is for “recreational purposes and not for medical purposes” and that “inherent limitations” may “cause some heart rate readings to be inaccurate”.

Despite these disclaimers, monitors that include a heart-rate reading can elicit consumer expectations. Disappointment with device performance has led to a class action lawsuit in California against Fitbit, alleging that its heart-rate monitors are “grossly inaccurate and frequently fail to record any heart rate at all”.

So how do optical heart-rate monitors work, and why aren’t they always accurate?

How they work

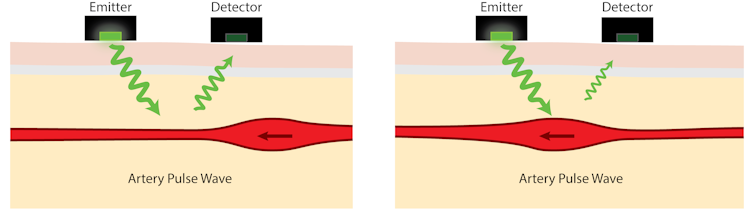

The science behind optical heart-rate monitors is something called photoplethysmography (PPG): the measurement of artery volume using light. When light emitted by the monitor enters the skin, most of it is absorbed by body tissues, but some is reflected. The amount of reflected light depends on several factors, one of which is the volume of arteries near the skin’s surface.

Blood in the arteries absorbs light better than the surrounding body tissues so, as arteries contract and swell in response to the pulsating blood pressure, the intensity of the reflected light rises and falls. PPG devices detect this variation in reflected light and use it to estimate heart rate.

FIGURE 1 Optical heart rate sensing. Left: lower pressure preceding the pulse wave means narrower arteries and less absorption (higher reflectivity) of the green light source. Right: a higher blood pressure pulse causes wider arteries and more light absorption (lower reflectivity). Source: Tim Collins.

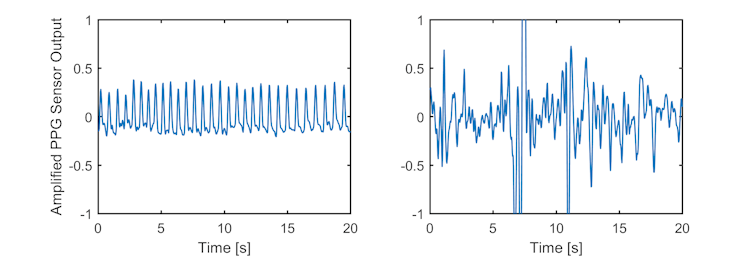

The reflected light variation due to heart rate is typically no more than about 2% – a change that is imperceptible to the human eye. Physical movement, however, causes much greater effects, so much so that even small movements can make the much weaker pulse signal impossible to detect. Signal losses caused by movement at the sensor-skin interface can mean that simply walking can be enough to mask the pulse signal.

FIGURE 2 PPG sensor outputs. Left: while sitting still, showing an easily identified heart-rate signal. Right: the same sensor minutes later while walking. Source: Tim Collins.

It can be very difficult to accurately estimate heart rate from a corrupted PPG signal. Mathematical techniques can help in some cases, but often the motion interference and heart-rate signals overlap so much that the two are impossible to separate. For example, repeating interference signals caused by walking at 100 steps per minute can be indistinguishable from a heart rate of 100 beats per minute.

To reduce the chances of incorrect heart-rate readings, a common strategy is to stop recording when high levels of motion interference are detected. Unfortunately, this means that during periods of vigorous exercise, when many users are most interested in their heart rates, their PPG activity monitor might fail to record anything at all.

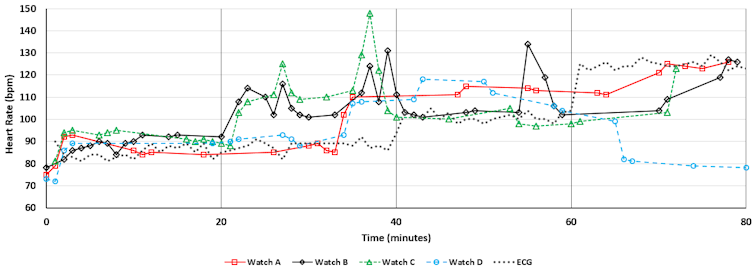

Detecting when a signal is corrupted is also not easy. Inevitably, some bad estimates of heart rate will be recorded in error. In recent experiments we conducted, using four identical heart-rate monitors (two on each wrist), we observed recorded heart rates as low as half and as high as nearly double the person’s actual heart rate. Consistency between the devices varied depending, largely, on the level of activity.

FIGURE 3 Example of experimental results comparing four identical Garmin VivoSmart 3 monitors during an 80-minute treadmill walking exercise. Walking speeds were increased every 20 minutes, from slow (2.4km/h) to vigorous (6.4km/h). Electrocardiogram (ECG) data for comparison was recorded using a chest-strap heart-rate monitor. Source: Tim Collins.

Cheap and convenient

The popularity of optical heart-rate monitors that can be worn on the wrist is largely due to the convenience and low cost of the devices. However, during periods of physical activity, accurately estimating a person’s heart rate using these devices remains challenging. And we should not expect dramatic improvements in reliability unless there are fundamental changes in the sensor technology. This is not a reflection of the quality of the devices, but rather an inevitable technological limitation of optical sensing.

![]() Whether the labelling of these devices as a “heart-rate monitor” risks creating unrealistic expectations is a different matter.

Whether the labelling of these devices as a “heart-rate monitor” risks creating unrealistic expectations is a different matter.

About the authors

Tim Collins is senior lecturer in electronic engineering at Manchester Metropolitan University, Ivan Miguel Pires is a PhD researcher at the University of Beira Interior, Salome Oniani is a PhD researcher at Georgian Technical University, and Sandra Woolley is senior lecturer in software and systems engineering research at Keele University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.